HokkaidoMarshland Visit ArticleGenya, who posted this, wrote a climbing diary of Mt. Asahidake!

Now, please enjoy Genya's article!

table of contents

Introduction

"The Northern Land" is a nice-sounding phrase.

I was invited to the top of the earth.

However, after giving up twice in the past, this year I decided to finally reach the pinnacle of the earth, Mount Asahidake.

Mornings in Hokkaido come earlier than in Honshu, and it's already light out.

Looking outside, I saw a cloudless blue sky. Third time's a charm. As I got off the cable car at Sugatami Station, a mountain towered in front of me on the promenade.

So this is what Mt. Asahidake is like.

Looking at it again, it's a massive mountain.

Enjoying mountain climbing in fine weather is a blissful experience.

According to the weather board, the wind was 3m from the south, visibility was good, and the temperature was 13°C, perfect weather for a few mountain climbing trips per year.

Last year on the promenade, I jumped left and right to avoid getting wet, but this year my feet felt like they were being sucked into the peak in front of me.

Overview of Mt. Asahi that I encountered

Mount Asahi is written as "Mount Daisetsu" in Kyuya Fukada's "100 Famous Mountains of Japan."

He wrote that from the summit you could see all the way to Shiretoko, 200km away in a straight line.

I saw it too.

The unobstructed summit of Hokkaido stands at 2,291m above sea level.

1. Geology in general

The current summit was formed approximately 5,000 years ago, and the western side of Mt. Asahidake collapsed about 3,000 years ago, creating the horseshoe-shaped Jigokudani crater.

Furthermore, steam explosions have occurred frequently since 1,000 years ago, forming a group of small craters such as Sugatami Pond.

The most recent phreatic eruption at Asahidake was approximately 250 years ago, and steam is still rising from the Jigokudani crater today.

2. Overview of vegetation

Many of the mountains in the Daisetsu mountain range are around 2,000m above sea level, but due to their high latitude they have a harsh alpine environment comparable to those in Honshu at 3,000m.

As a result, the foothills are covered with a vast forest of conifers and broad-leaved trees, mainly consisting of Ezo spruce and Todo fir.

As the altitude increases, the forest appearance changes from coniferous forest to birch forest, then to the tree line and a zone of pumila pines, where communities of alpine plants can also be seen.

Climbing Record

Now that the snow has melted, alpine plants begin to bloom all at once.

As far as I could see, near Sugatami Pond I saw yellow rhododendrons (white), Siberian kozakura (red), and yellow buttercups.

In July, the Acanthus edulis flowers all at once.

▼Around the walking path, you can see grasslands, flowers here and there, creeping pines, and snowfields here and there.

First, there is the white flower, Rhododendron amplexicaule, which is 3 to 4 cm in diameter and 10 to 30 cm in height.

This evergreen shrub grows naturally in grasslands and areas of Japanese stone pine, and large colonies can be seen around Sugatami Pond.

They bloom about two weeks after the snow melts, forming pale yellow clusters.

The flowers are mostly cream in color, but white and pale red ones can also be found.

▼Next is the Ezo Kozakura.

This red flower grows in wetlands and moist grasslands, blooming beside snowfields and sometimes growing in clusters.

Compared to the Hakusanzakura, the serrations on the leaves are broader and the incisions in the petals are slightly shallower.

▼The yellow one is the Meakankinbai, a perennial plant that grows in the gravel areas of the Shiretoko, Akan, and Daisetsu mountain ranges and Mount Yotei.

It is short and grows close to the ground.

The leaves are greyish green and divided into 3 leaflets.

The tip of the leaflet is largely divided into three parts.

The petals are spatula-shaped with rounded tips. The sepals are large and the gaps between the petals are wide, making them very noticeable.

The climb to Mt. Asahi begins at Ishimuro 5P, at an altitude of 1,417m.

We start climbing up the rocky scree.

The flower field from earlier changes into a rocky area.

It's a clear day today, all the way to the summit.

If you look through binoculars, I think you might even be able to see the climbers on the summit.

▼We got off the ropeway at Sugatami Station and started walking along the hiking trail.

This is the full, imposing Mount Asahi seen from the front.

▼ Mirror Pond Half of it is buried in snow.

▼Steam rises from Jigokudani on the left.

According to the Japan Meteorological Agency's overview of volcanic activity, volcanic activity has remained calm, with the height of the steam from the Valley explosion crater remaining below 100m, and fumarolic activity remaining low.

No signs of an eruption are observed.

There are no changes to the eruption forecast (eruption alert level 1, please note that it is an active volcano).

▼ Monotonous climb up the scree slope P-6 Elevation 1995m

The ridge is wide and there are many paths, making it difficult to choose a route during a blizzard.

▼Although it is a steady climb, if you move your eyes from the rugged north side to the south, you will see scattered snow fields beyond the rubble all the way.

The forest belt continues, and beyond that, across the deep valley of the Chube River, the mountain ranges of Koasahi and Chubetsuke form the roof of Hokkaido.

▼The ridgeline is clear.

We're almost to the summit, at an altitude of around 2,200m.

It's rare to see a mountain whose summit is so clearly visible.

Climbers are clearly visible.

▼The summit of Mt. Asahidake

We reached the summit of Mt. Asahi in about 2:20, covering an elevation difference of 690m.

I finally reached the top of Mount Asahidake, the leader of the great mountain ranges that make up the roof of Hokkaido, for the third time.

View from the top

From the summit on a clear day we had unobstructed views as far as the eye could see.

View of the West The mountain trail we just climbed

To the west, across the Jigokudani snowfield, the ridge on the left is the ridge we just climbed up, Sugatami Pond, Meoto Pond, and beyond the virgin forest, you can see Chubetsu Dam and Chubetsu Lake.

▼Are those the Soya Hills in the hazy distance to the north?

▼ To the east, Mt. Ushiroasahi is right in front of you, and in the distance you can see the Daisetsu ridges, including Mt. Arai and Mt. Hokkai.

▼ Reeds in the marshland beside the boardwalk to Sugatami Station. You can see the beginning of a 1m layer of peat 1000 years later, 1mm per year.

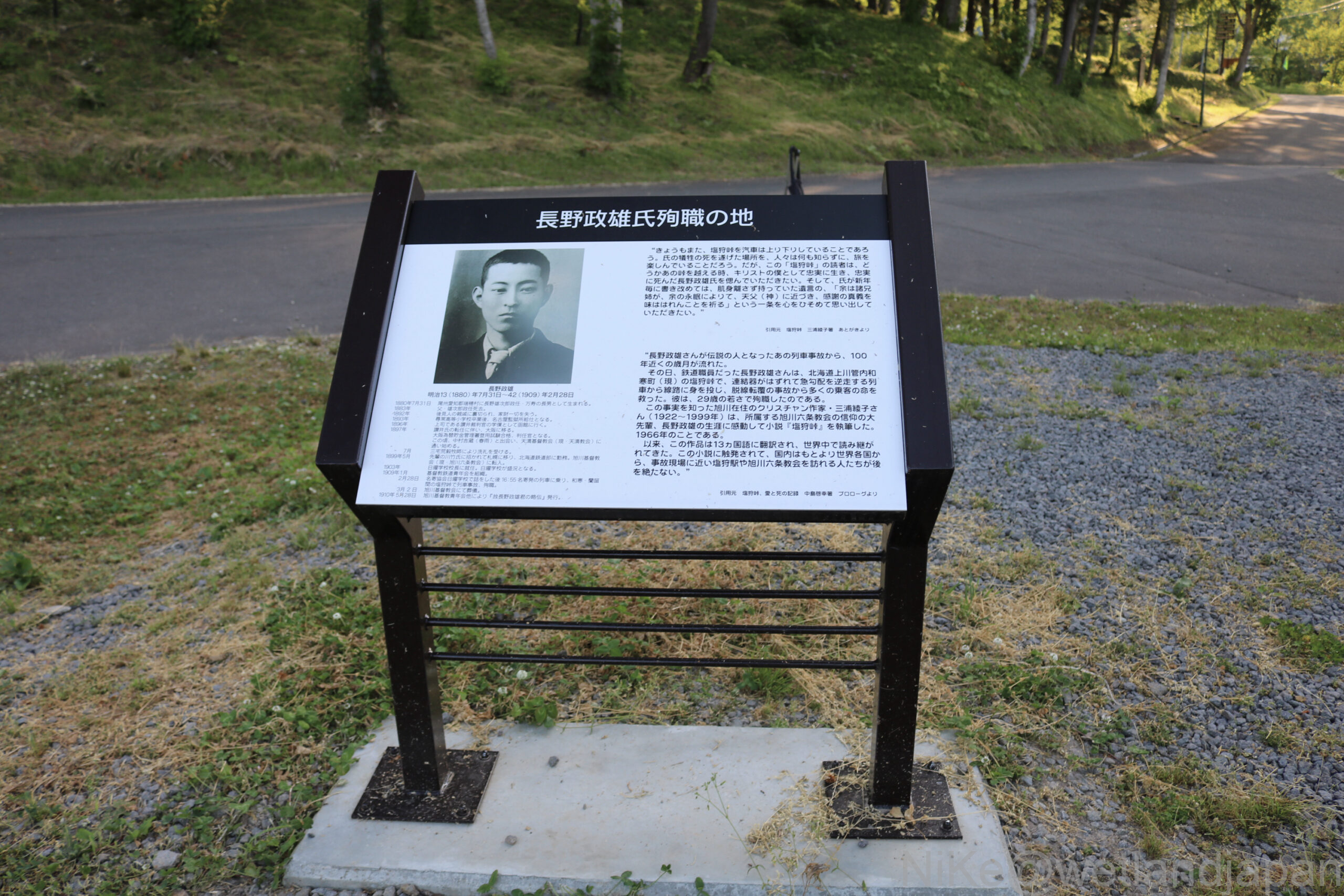

▼ Monument marking the site where Masao Nagano died in the line of duty

After descending the mountain, I got off at Shiokari, the seventh stop on the Soya Main Line from Asahikawa, at the foot of the hills, and saw the memorial to Nagano Masao, the protagonist of Miura Ayako's novel Shiokari Pass, who risked his own life to stop a train and save the lives of passengers.

Afterword

According to Google Earth, Mt. Asahi appears to be the vanguard mountain of the Daisetsuzan mountain range.

To the northeast, beyond Mt. Mamiya, you can see what appears to be the remains of a huge crater, and on an old map, the Kuril volcanic belt stretches from here to the Kuril Islands.

The day was clear and I was able to enjoy the subarctic forest, the alpine flowers that were beginning to bloom all at once, the volcano emitting steam, and the magnificent views as I reached the summit, touring the places that are the subject of my novel. It was a wonderful memory to be able to reach the top of this northern land, a place I don't think I will ever set foot on again.

Asahidake is part of Daisetsuzan National Park, Japan's largest national park, but the low temperatures and strong winds within the vast park make it difficult for snow to accumulate, and there is permafrost in areas where there are few shrubs.

This seems to be the case around Mt. Hakuun.

It is often said that "mountains will not run away," but as global warming progresses, vegetation and natural shapes may change, and precious scenery may disappear.

I will strive to maintain my physical and mental strength and return to witness the beautiful nature.

References etc.

Source: Biology Lecturer Toru Omori Official Site 108 Japanese Flora

(4Traavel,jp) Japan Meteorological Agency Asahidake Visitor Center Google Earth Environment Agency Hokkaido University

With excerpts from each website

There are also photos with people in them, but they are unrelated.